What is Anxiety Disorder’s ?

Anxiety, is complex and mysterious, and in some ways the more we are learning about it with progress in technology and research the more baffling it is seeming. Anxiety is a specific type of disorder but it is more than that. It is an emotion implicated so heavily across the full range of psychopathology, that any discussion that explores its general nature both biological and psychological will not do it justice, because it differs from individual to individual. There is a somewhat different but very closely related emotion and that is, the emotion of a panic attack which we now believe is fear and occurs when there is nothing to be afraid of and therefore at an inappropriate time.

Officially as it is defined anxiety is a negative mood state characterised by bodily symptoms of physical tension and by apprehension about the future. In us as humans it can be a subjective sense of unease and a set of behaviours where, the individual feels both worried and anxious at the same time and there is a psychological response originating in the brain and that is reflected in elevated heart and muscle tension.

Anxiety is not a pleasant emotion and many times we have questioned as to why do we seem programmed, being human beings to experience it almost every time we do something important. Surprisingly at times anxiety is good for us at least in moderate amounts. We have known for over a century that we perform better when we are a little anxious. It becomes a problem when it goes out of our control. In short physical and intellectual performances are driven and enhanced by anxiety.

We remember a case of a 25-year-old young lady who had come to us when she had her first attack. It was a few weeks after she had gone home from the hospital. She had - had her appendix removed. The surgery had gone well and she was not in any danger which is why she did not understand what happened to her. But one night she went to sleep and woke up after a few hours. In her own words she was not sure how long but she woke up with a big sensation and a feeling of apprehension as described by her. Mostly when she described it to us she said that her heart had started pounding and her chest had started hurting and it felt as if she was dying and that she was having a heart attack. She also mentioned that she felt kind of queer as if she was detached from the experience. We recall her mentioning that it seemed like her bedroom was covered with a haze and after that she ran to her sisters room but felt like she was a puppet or a robot who was under the control of somebody else while she was running. She mentioned that what scared her most as much as she was frightened herself and that is when she sought an appointment with us.

This sudden overwhelming reaction is known as a panic attack after the Greek God Pan who terrified travellers with bloodcurdling screams. In psycho pathology a panic attack is defined as an abrupt experience of intense fear or acute discomfort, accompanied by physical symptoms that usually include heart palpitations, shortness of breath and possible dizziness. Unexpected attacks are very important in panic disorders and the fear is so intense that people can begin to feel as if they are going to have a heart attack. There can be biological, social, psychological, and social contributors that can create anxiety and related disorders. The biological contributions are showing an increasing evidence that we inherit a tendency to be tense, uptight and anxious. The tendency to panic also seems to run in families and probably has a genetic component that differs somewhat from genetic contributions to anxiety. As with almost all emotional traits and psychological disorders no single gene seems to cause anxiety or panic. Instead contributions from collections of gene's in several areas on chromosomes make us vulnerable when the right psychological and social factors are in place. Furthermore a genetic vulnerability does not cause anxiety and/or panic directly - that is stress or other factors in the environment can turn on the genes. We also know now that anxiety is associated with specific brain circuits and neurotransmitter systems.

However the most important contributors to anxiety disorders are psychological contributions. In childhood we acquire an awareness that events are not always in our control. The continuum of this perception may range from total confidence in our control of all aspects of our lives, to deep uncertainty about ourselves and our ability to deal with upcoming events. If someone is anxious about school work for example, they may worry whether they will do poorly in the next exam even though all their grades would be above 70 or 80%. A general sense of uncontrollability may develop early as a function of upbringing and other disruptive or traumatic environmental factors. We have also seen that parents who interact in a positive and predictable way with their children by responding to their needs, particularly when the child communicates needs for attention, food, a relief from pain and so on - perform an important function. These parents teach their children that they have control over their environment and their responses have an effect on their parents and their environment. In addition parents will provide a secure home base but allow their children to explore their world and develop the necessary skills to cope with unexpected occurrences Variety of evidence has accumulated supporting these ideas.

A sense of control or a lack of food that develops from these early experiences is the psychological factor that makes us more or less vulnerable to anxiety in later life. Most psychological accounts of panic as opposed to anxiety invoke conditioning and cognitive explanations that are difficult to separate. When a strong fear response initially, occurs during extreme stress, perhaps as a result of a dangerous situation in the environment, if it is left alone this emotional response then becomes associated with a variety of external and internal cues. In other words these cues or conditioned stimuli, provoke the fear response and an assumption of danger, even if the danger is not actually present. So it is really a learned false alarm. This is the conditioning process as we collect through our childhood. External cues are places or situations similar to the one where the initial panic attack occurred. Internal cues are increases in heart rate or respiration that were associated with the initial panic attack, even if they are now the result of normal circumstances, such as exercise. That's when your heart is beating fast you are more likely to think of and perhaps, experience a panic attack than when it is beating normally. Furthermore one may not be aware of the cues or triggers of severe fear .

Social contributions to a stressful life are even stronger than our biological and psychological vulnerability. Most initial contributor’s or conditioner’s are social and interpersonal in nature - like marriage, divorce, difficulties at work, death of a loved one, pressure to excel in school and so on. Some might be physical such as injuries or illness. The same stressors can trigger physical reactions such as headaches or hypertension, and emotional reactions such as panic attacks. The particular way we react to stress seems to run in families. If you get headaches when under stress, chances are other people in your family also get headaches. If you have panic attacks other members of your family probably do also. This findings suggest a possible genetic contribution at least to initial panic attacks.

We also find that there is a comorbidity of anxiety and related disorders. The dual occurrence of two or more disorders in a single individual is referred to as comorbidity. The high rates of comorbidity among anxiety and related disorders and depression emphasise how all of these disorders share the common features of anxiety and panic. They also share the same vulnerability as the biological and psychological ones that lead people to develop anxiety and panic problems, the various disorders differ only in what triggers the anxiety and perhaps the beginning of panic attacks. Of course, if each patient with an anxiety or related disorder also had every other anxiety disorder, there would be little sense in distinguishing among the specific disorders. But this is not the case, and although rates of comorbidity are high they vary somewhat from disorder to disorder. If somebody is under a lot of pressure, particularly from interpersonal stressors, a given stressor could activate that persons biological tendencies to be anxious and the persons psychological tendencies do feel that they might not be able to deal with the situation and control the stress. Once the cycle starts, it tends to feed on its self so it might not stop even when the particular life stressor has long since past. Anxiety can be general, evoked by many aspects of our life. But it is usually focused on one area such as social evaluations or grades. Panic is also a characteristic response to stress that runs in families and may have a genetic component that is separate from anxiety. Furthermore anxiety and panic are closely related. Anxiety increases the likelihood of panic. This relationship makes sense from an evolutionary point of view, because sensing if there is a possible future threat or danger (anxiety) should prepare us to react instantaneously with an alarm response if the danger becomes imminent. Anxiety and panic need not a go together, but it makes sense that they often do, due to the overlap of symptoms.

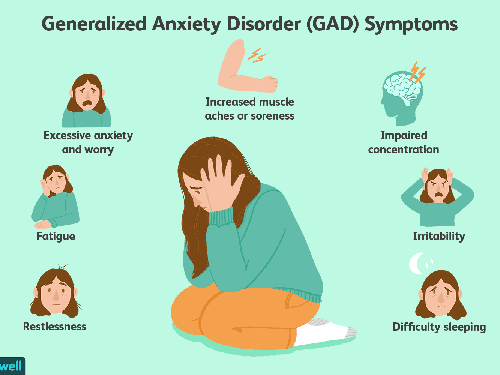

Disorders that are traditionally grouped together as anxiety disorders include generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder and agoraphobia, specific phobia, and social anxiety disorder, as well as two new disorders primarily separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism. These specific anxiety disorders are complicated by Panic attacks or other features that are the focus of the anxiety. But in generalised anxiety disorder the focus is generalised to the events of every day life. Most of us worry to some extent, and worry can be useful. It helps us plan for the future, and make sure that we are prepared for that test, or doublecheck that we have thought of everything before we leave home for the holidays. But the issues begin to arise when we start worrying indiscriminately about everything. And furthermore it is even more stressful if the worrying is unproductive. What if no matter how much we worry we still can't seem to decide what to do about the upcoming problem or situation. And what if we can't stop worrying, even if we know it is doing us no good and probably making everyone else around us miserable. These are the features that characterise a generalised anxiety disorder. Generalised anxiety disorder is in many ways the basic syndrome that characterises every anxiety and related disorder. In fact now there are at least specific criteria that must last six months for a minimum to be categorised correctly. Even if the upcoming challenge is a big one, as soon as the event is over we normally stop worrying, however if we go from one crisis to another crisis then the physical symptoms associated with generalised anxiety disorder begin to become permanent and this can cause a significant amount of distress in us as human beings. Generalised anxiety disorder also differs somewhat from those symptoms that are associated with panic attacks and panic disorder. Whereas panic is associated with autonomic arousal presumably as a result of a sympathetic nervous system surge, like an increased heart rate, palpitations perspiration and trembling generalised anxiety disorder is characterised by muscle tension and mental agitation as well as susceptibility to fatigue - probably the result of chronic excessive muscle tension - some irritability and difficulty in sleeping. Focusing one's attention is difficult as the mind quickly switches from one crisis to another crisis. Anyone who has a generalised anxiety disorder will worry about minor every day life events, a characteristic that distinguishes generalised anxiety disorder from other anxiety disorders. When I asked do you worry excessively about minor things, hundred percent of individuals with generalised anxiety disorder will respond with a yes, compared with approximately 50% of individuals whose anxiety disorder falls within other categories. Major event' can quickly become the focus of anxiety and worry too. Adults typically focus on possible misfortune to their children ,family, health, job responsibilities and more minor things such as household chores or being on time for appointments. Children with generalised anxiety disorder most often worry about competence in academic, athletic or social performance, as well as family issues. Older individuals typically seem to be concerned about health and they also have difficulty sleeping with seems to make the anxiety worse. The treatment of generalised anxiety disorder is now possible and available treatments such as both drugs and psychological intervention are reasonably effective. Globally we now believe that in the short term psychological treatments seem to give the same benefit as drugs in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder - but we are now realising that psychological treatments are more effective in the long run. We now know that individuals who have generalised anxiety disorder seem to avoid feelings of anxiety and the negative effect associated with threatening images, feeling’s, flashback’s and we now have designed treatments to help clients with generalised anxiety disorder process the threatening information on an emotional level, so that they will feel rather than avoid feeling anxious, and these treatments have other components also like teaching clients how to relax deeply to combat tension.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is an example of one type of psychotherapy that can help people with anxiety disorders. It teaches people different ways of thinking, behaving, and reacting to anxiety-producing and fearful objects and situations. CBT can also help people learn and practice social skills, which is vital for treating social anxiety disorder.Cognitive therapy and exposure therapy are two CBT methods that are often used, together or by themselves, to treat social anxiety disorder. Cognitive therapy focuses on identifying, challenging, and then neutralising unhelpful or distorted thoughts underlying anxiety disorders. Exposure therapy focuses on confronting the fears underlying an anxiety disorder to help people engage in activities they have been avoiding. Exposure therapy is sometimes used along with relaxation exercises and/or imagery.CBT can be conducted individually or with a group of people who have similar difficulties. Often “homework” is assigned for participants to complete between sessions.

There are different options for different individuals, and no one size fits all glove is available. Once an individual enters into therapy, normally it should take a good psychologist one or a maximum of two sessions to understand how to help the client, and the client in turn should be receptive and open to suggestions as well as interpretations so that they are able to work along with the therapist to find a remedy for the underlying reasons that are causing the anxiety disorders or which are leading to panic attacks as these can be extremely debilitating on a day-to-day basis.